THE MILL Summer 2020

Newsletter of the Friends of High Salvington Windmill

Mill closed for 2020 season

Welcome to a special newsletter published by the High Salvington Windmill. Most of you will already know of the very sad decision taken by the Board not to open at all this season. As the Covid-19 crisis unfolded, at first, we thought we might be able to salvage our late summer events, and possibly the fete. But by April it was clear to all that, even with the easing of restrictions, public gatherings would not be allowed this summer. We could not ensure correct social distancing even for small groups, given the confined space inside our mill. We also needed to consider the health of our volunteers, many of whom are over 70, some with underlying health issues. We hope you will enjoy reading some stories and anecdotes about our mill, and others in the local area.

ooOoo

A look back at the story of our mill and those that went before

We hope you will enjoy this collection of items from the past. They include anecdotes and stories from the archives.

Fire at the mill

An entry in The Sussex Weather Book by Ogley, Currie and Davison tells us that on November 23rd 1755 “…A windmill in the parish of Durrington … was set on fire by lightning … which, in a short while, consumed the same ….”

The Archive Group decided to investigate further and found a mention in the Kentish Post and the Brighton Herald, which further informed that with the mill, several loads of corn were also destroyed. We do not believe that there was a round house then, so the corn must have been stored inside the mill. It seems fairly certain that the mill then stood on an open hardwood (oak) trestle. Eighteen months after the fire, the mill was insured for £250 with the ‘Sun Fire Office’ for a premium of £5. Over the years, the mill was substantially and expensively updated, with a roundhouse being built to safeguard a trestle made of softwood, the buck enlarged, and a pair of spring shutter sails replacing a pair of common sails. Business must have been good!

Milling through the ages

Indentured labour

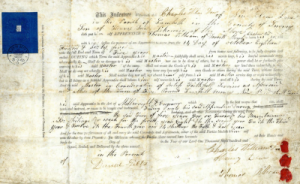

The Mills archive holds a wonderful document. It is an indenture between the millwright and engineer Thomas Pilbeam, and his new apprentice, Charles William Dew. Dated 14th October 1865, it agrees that Charles Dew will work for five years, and promises his good and lawful behaviour. In return he will be taught ‘The Art of the Millwright and Engineer’. It also agrees to an increasing rate of pay as his skills and abilities develop throughout the apprenticeship. He begins on six shillings a week and ends on fourteen shillings a week in his fifth year of employment.

It seems Charles had a successful apprenticeship. In a reference, Thomas Pilbeam rues the fact that he does not have enough work for him. It seems that Charles was able to gain employment. A later reference from the foreman at Medina Mills explains that he worked to ‘full satisfaction’ as a millwright and engineer, leaving to work on another mill under construction.

| Sussex Weekly Advertiser December 5th 1774

WANTED A MILLER, one that is a sober man and can write. It is not material that he is quite master of the Business or not. Apply to William EDE at Shermanbury, near Steyning. |

Muscle Power

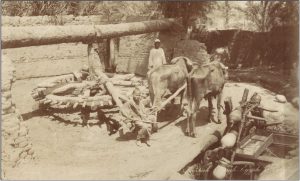

Very early mills used man and animal power to raise water for irrigation and to turn stones to grind all kinds of products such as sugar cane, beans, corn, etc. The image on the right shows how water was raised in North Africa. Driven by two bullocks the machinery moved earthenware pots in a loop, scooping the water up from a well. Another example from the archive shows a human watermill in China employing two workers to operate a treadwheel/scoop wheel contraption to irrigate paddy fields.

ooOoo

Good guy, bad guy?

Throughout the ages, the role of the miller has been subject to all sorts of stories and stereotypes: millers have been slandered, satirised, respected and romanticised all in equal measures.

A volume called The Mills of Man by George Long (available in the archive) contains an account attesting that at one time, the jobs of milling and smuggling often went hand in hand.

Mr Long describes how, at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries “when that nefarious traffic reached its zenith”, the miller had an important role to play in the highly-organised smuggling trade. The miller was “frequently the individual responsible for the actual delivery to the consumer of the articles ordered. The reason for this was that the mill was situated in every village – either wind or water – and could easily deliver contraband articles concealed beneath the sacks of grain or flour which formed its legitimate trade. Further, those small mills which had no delivery vehicles of their own could hand the articles to the callers as they brought their grist and took away their flour.”

So it seems that millers took a leading part in the work of delivering orders to the customers in towns and villages – an ingenious method indeed! This business would not have taken place completely secretly: often the whole village would have been in on it as many of them would have benefitted, as we hear in Rudyard Kipling’s poem A Smuggler’s Song: “Brandy for the Parson, ‘Baccy for the Clerk”. Those that didn’t benefit chose to subtly turn their heads:

“Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie –

Watch the wall my darling as the gentlemen go by!”

Stories of the smuggling days are particularly rife around the Hampshire and Sussex coastline, In its heyday smuggling was common across the whole of the southern coast of England, from Falmouth to Folkestone and anywhere in between.

We are indebted to the Mills Archive newsletter for these stories. If you want to know more, look them up at this link: https://millsarchive.org/

ooOoo

Miller’s tomb at Highdown

The isolated tomb of John Olliver on Highdown Hill has been a focal point for gossip, jokes and rumour for over two hundred years. Olliver was a prosperous miller who built his own tomb in 1766 – 27 years before his death. The tombstone reads: “For the reception of the body of John Olliver, when deceased to the Will of God: granted by William Westbrooke Richardson esq., 1766”. But there’s more.

Olliver reportedly kept his casket under his bed all the years between securing the burial plot and actually entering the great beyond. Locals suspected that he was a smuggler, using sails arranged in code on his windmill to tell of his shipments and storing the illicit goods in his casket and at his future gravesite. We have to wonder what exactly he might have been smuggling!

Over 2000 people turned up at his funeral to witness his passing, and rumour has it, he was buried face down. Apparently, the world would be turned upside down when the last judgment came, and his position underground would ensure he was the right way up! John Olliver was not associated in any way with our windmill in High Salvington, despite the fact that they could clearly see each other across the fields between their hills.

Sources: various including BBC Southern Counties and Dusty Old Things.

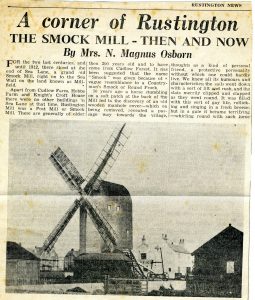

Rustington Smock Mill

One of our Facebook followers posted a newspaper article about the mill at Rustington which existed up to 1912. Rustington Mill stood at the end of Sea Lane. Apart from Cudlow Farm, Hobbs Farm and Knight’s Croft House, there were no other buildings in Sea Lane apart from Rustington Mill – a Post Mill or Smock Mill.

According to the article, some of which we reproduce here, it had stood for two centuries. A passage leading to the village was discovered, thought to have been used for smuggling. The nearby houses had similar passages. Smuggling truly was rife in Sussex back in the 18th century!

Thanks to Rustington Past and Present for permission to reproduce this cutting.

| Sussex Weekly Advertiser 1774

October 24th WANTED A Miller who understand the Business and can be well recommended and can write. Apply to Mr. JOHN STOVELD at Steyning |

| Our Hampshire neighbour

Bursledon Windmill is Hamp-shire’s only working windmill, and a fascinating example of the county’s milling history. Built in 1813, after a period of dereliction it was restored and reopened in the 1990s as a working windmill and heritage attraction. ooOoo |

| Southern Weekly Advertiser, Monday, January 17th 1774

On Wednesday last one Combe a miller at Newhaven, was going from that place to Worth on horseback with a woman behind him. His horse took fright at something on the road when the woman too jumped off without hurt but unfortunately pulling Combe with her his foot hung in the stirrup and the horse dragging him a considerable distance he was horribly bruised that he died on Saturday. October 17th To be sold by AUCTION On Wednesday the 26th of October Instant, at the Sign of the Wheel at Westfield Sussex except disposed of by previous Contract before A WATERWHEEL and HUST and a Cogwheel and Boulter and the Building of a Water Mill thereto belonging. For further particulars enquire of Mr. HAYWARD Miller at Wartlington. August 13th Whereas the Ponds at BREAD POWDER MILLS near BATTLE in the county of Sussex have lately been several Times robbed and great Quantities of Fish stolen by Poachers and unjustified Persons in the Night Time. A Reward of TEN GUINEAS is offered to any Person who shall discover or give information against the offending Person or Persons so that they may be brought to Justice … ooOoo |

| From the Southern Weekly Advertiser,

February 7th 1774 On Friday se’ennight Battle Powder Mill blew up, but happily no lives were lost. February 14th A few days since died at his house in Chichester Mr. Wm Woods, one of the joint proprietors of the large tide mill at Seaford; this gentleman has for many years laboured under heavy excruciating tortures from that disease of the Stone which he bore with great Christian fortitude; and within a few days of his death he declared that when dead he might be opened which was accordingly done and a Stone of above eleven ounces was taken out of his bladder. Lewes July 4th On Wednesday last as a lad, son to Mr Hoather, miller of the above place [Brighthelmstone] was chopping a bat with a handbill it unfortunately fell on his wrist which thereby received such a desperate wound, that it is fear’d his hand must undergo a Amputation. Thanks to Wendy Funnel, our archivist, for these gems. |

Stories from our guides

Backhanded compliment!

At the conclusion of the tour a lady turned to me and said, “Well, that was a lot more interesting than I thought it was going to be….” (Greg).

Out of the mouths…

One young and apparently very well-read visitor asked me why the mill hadn’t blown up, because

– they were doing long hours milling after the harvest and would need light.

– but they only had candles or oil lamps,

– and a working flour mill is full of flour dust – which is notoriously flammable. (Paul)

Perhaps they simply made the best use of summer daylight that they could. Or maybe they could see in the dark. Or was it just luck? (Ed.)

Another guide reported that a young visitor to the mill at Singleton asked about how everything worked. She listened carefully as our guide showed her the grain, the stones, the bran and the flour. Asked if she had any questions she enquired “why do you have hairs growing out of your nose?”

The same guide has often been asked about the ‘electric motor that drives the sails.’ Of course, there is no motor – the wind is the driving force. And to some of today’s visitors, it seems an alien concept. You never know what questions may be asked or what explanations you might be called upon to resolve. (Bob)

ooOoo

Follow us on Facebook. Just look for High Salvington Windmill and “like” our page to see news about the mill and the planned events throughout the year.

A word from our Acting Chairman, Jeff Best

At this troubling time, when we are physically distanced from friends and family and the future is uncertain, I am very grateful to our maintenance and management teams who have adapted, with aplomb, to the new “normal”. The grass is still being cut and hedges kept in excellent trim. The mill is still being turned into the wind and the sails rotated regularly to balance wear. The buildings are being checked and a weather eye kept on known maintenance issues. I regret that this season, we cannot welcome visitors and many of our volunteers, but your health is more important. I look forward to the time when this infection is under control and we can resume operations. In the meantime, stay safe, and know that we are doing all we can to keep the mill and engines well maintained and the site well-groomed ready to welcome everyone back once this is all behind us. Finally, I would like to make special mention of Ian Fairclough, who has been managing maintenance diligently for the last few years, and Lucy Brooks, who is putting extra effort into producing an additional newsletter to remind us all of the heritage treasures we are all committed to preserving for those who follow us.

ooOoo

| A miller’s poem

The windmill is a couris thing Compleatly built by art of man To grind the corn for man and beast That they alike may have a feast

The mill she is built of wood, iron, and stone, |

| Therefore she cannot go aloan;

Therefore, to make the mill to go, The wind from some part she must blow.

The motison of the mill is swift, The miller must be very thrift, To jump about and get things ready, Or else the mill will soon run empty. |

‘The Mill’ is edited by Lucy Brooks. 01903 691945